GET TO KNOW OUR HISTORY

The Kunene Region of northwest Namibia is home to one of southern Africa’s great conservation success stories. Following independence (1990), the Namibian government formally extended rights over wildlife and tourism to local communities inhabiting communal land. Namibia’s ‘communal conservancies’ are a form of community-based natural resource management (CBNRM) land tenure, whereby self-defined communities engage in wildlife management policies and practices for their own socioeconomic benefits. Within each communal conservancy, economic benefits are derived from hunting and tourism and accrue directly to residents, who then decide how this communal income will be apportioned. The conceptual force behind this effort to combine wildlife management and rural livelihood development is the premise that when communities stand to realize economic benefits from natural resources, then sustainable resource management is more likely to occur. Namibia’s first communal conservancies were gazetted in 1998. There are currently almost 90 conservancies in the country. Since the start of the conservancy system wildlife populations have grown, hundreds of community members have served in conservancy leadership positions, and the communal conservancies have brought tens of millions of dollars into the Namibian economy

The motive forces for this ongoing conservation success story reside in the colonial and apartheid era preceding Namibian independence. Namibia’s communal conservancies were developed as a rebuke of governmental practices which often overlooked, and sometimes actively fought against, the rights and livelihoods of the country’s African residents. This was particularly true in the northern Kunene (formerly Kaokoveld) which lay beyond a veterinary fence running across the country delimiting the officially-controlled ‘Police Zone’ from the underdeveloped hinterlands. Prior to independence, the rights to wildlife had been controlled by South African and South West African colonial governments. When local residents hunted game species, as they had long done, they were officially guilty of poaching. However, because actual wildlife conservation oversight was limited during apartheid, management of wildlife and control of wildlife consumption was sorely lacking. Because trade beyond the region was largely cut-off from the rest of South West Africa and South Africa, and most households relied on small-scale agropastoralism, survival often meant heading to the bush and hunting for the pot.

Concerned that many wildlife species, such as the desert-adapted elephant (Loxodonta africana), black rhinoceros (Diceros bicornis), and African lion (Panthera leo), might be exterminated, a small group of dedicated local conservationists began working with traditional authorities during the 1980s. The goal was to innovate ways that communities could fill the vacuum of responsibility for conserving wildlife. Because traditional authorities maintained local political power and still claimed ownership tenure over much of the region, conservationists worked closely with them to develop a community game guard (CGG) program, whereby local residents, in many cases ex-poachers, monitored wildlife populations and reported to traditional authorities. While CGGs and traditional authorities had no officially-recognized enforcement rights, they were able to apply social pressure and report incidents to government officials. This early form of monitoring and enforcement, and informal ownership, before there was any possibility of monetary benefit, was central to the success of the later conservancy system.

After independence a socially-inclusive process began bringing rights to wildlife back to the local people. The Kunene Region has since become an international tourism and hunting destination of note. No longer alienated from wildlife, local people, as communal conservancy members, are playing an increasingly central role, not only in executing management practices, but in developing wildlife policy and in creating socially and ecologically sustainable institutions to grow local livelihood prospects.

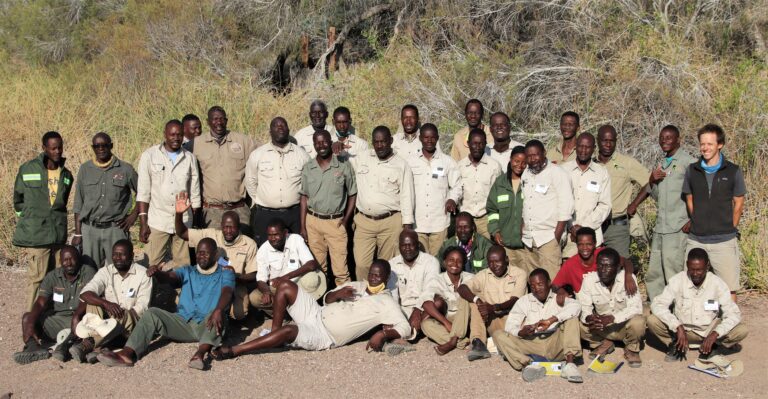

Our work focuses in particular on the conservation of the region’s desert-adapted lion population. Building upon the success of the CGG program, the Lion Rangers are locally-employed conservationists who receive additional training and support to help mitigate and manage human-lion conflict.

While the legacies of apartheid-era governance have not been entirely erased, conservancy residents continue to work alongside local conservationists to build towards a future in which wildlife and local people can share one of the world’s special places.

If you are interested to learn more about the region’s conservation history, books by Garth Owen-Smith and Margaret Jacobsohn are highly recommended.